“Our hardships was ended”

As July 4, 2022 approached I didn’t feel this country really deserved a “hooray for us” or even a weak-voiced “yippy” punctuated with a yummy picnic. Truthfully, the sourness weighed on me and I wanted to shake it. So, I sat down in the brilliant Lincoln City sun and wondered if there was anyone I could envision who embodied bravery, a drive for adventure, and a steady flow of optimism all of which I once considered the mandatory minimum of the American character. (Sounds cliche I know, but it was after all the 4th of July). I eventually wandered inside, opened my computer and looked at the work of my cousins, Joachim and Gina. They both research the stories of our Oregon pioneer family. And just what I needed, I found new material that Gina had uncovered, the words of my great-great-great Aunt, Laura Hawn Perkins Patterson (1835 – 1921).

After reading Laura’s story I felt lighter, a bit happier and figured her story should be shared here. Maybe it will do a little something for you too, dear readers, if you are feeling a bit down about this country. So here you go, here is the first part of Laura’s history – in her own words. I added footnotes to expand on parts of her story (which is not completely told here because later, as a young married woman, Laura’s life took a violent turn. I’ll pull together some of that information too. It is a classic Western tale of deceit and murder).

Here is Laura’s story told in her words:

I was born in Wisconsin near Green Bay September 1, 1835. These are my recollections of our trip to Oregon when I was 8 years old.

My parents1 lived in Franklin County, Missouri. They started to Oregon on May 10, 1843. They traveled by boat four days and laid over at Independence, Missouri. They bought our oxen there.

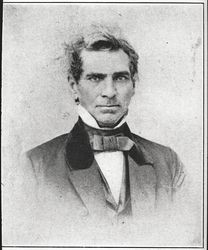

The company all gathered there—300 all told and started on May 18. Jesse Applegate2 was selected captain. We started on their way. We traveled by the compass—due west—a happy lot of people, all of one mind to go to a new country called Oregon. We had nothing to fear, we had plenty of grass for the stock. At night, they would drive the teams in a circle and make a corral of the wagons; the stock was turned out to feed until after supper. The camps were on the outside, and the stock was put in the corral for the night.

The people would spend their evenings around the campfires visiting, telling stories, singing and often dancing. Often the strains of a violin could be heard. We had no sickness or fear of Indians, all was well and happy. We had men hunting for game so had plenty of meat.

When we came to buffalo country, we had trouble with loose stock. They would have two men with guns go ahead of the wagons on horseback to look out for buffalo, if they were coming towards our wagon train; the signal was to come back posthaste with handkerchiefs tied to their guns. Then the teams would circle, and the stock put inside the corral. The men would shoot at the buffalo to get the herd to avoid our stockades. Sometimes one or more of the buffalo would be killed. At one time they nearly ran over the train as the buffalo turned toward our wagons.

The company kept men out hunting every day to keep us supplied with meat. When they killed a buffalo, it was divided with every family and the hides were cut in strips and wrapped around the running gear of the wagons if that was needed. Some of the hides were kept whole which came in handy later on. There were thousands of buffalo; it would look like the prairie was covered with them.

As we got further west, the grass became scarce, so the Captain [Applegate] divided the company—putting all those that had loose stock one day behind the other group. When we came to the Platte River, it was full banks.

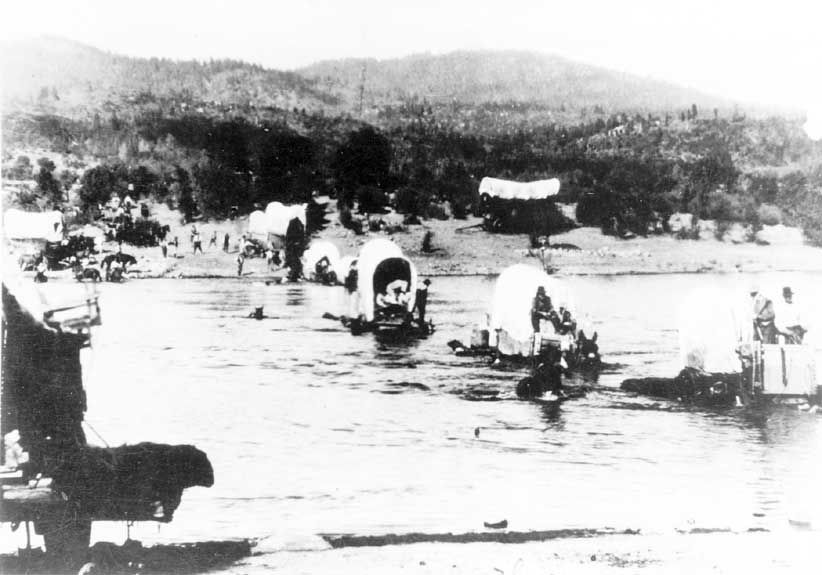

The Indians found a ford for the teams, but the wagons were all fastened together by tying each team to the hind end of the next wagon. Before crossing, they took out their entire load except the heavy irons such as chains and kettles. We lost many things during the crossing and others fared the same. Some of the wagons were taken off their wheels and boats were made to ferry the families and their freight. The buffalo hides were sewn together and put over the wagon beds to make them watertight. A man would swim ahead of the wagon with a rope and two men would swim behind and push. It took two or three days to get all of the families across the river. The last boat sank close to shore. With the help of the Indians, all was saved.

Through the country the prairie was bare except small sage brush and rag weed. The ground was white like ashes. The buffalo trails were several inches deep and it seemed we traveled diagonally across them for days. At night, camp would be by a stream. There was scarcely anything to burn. We would gather buffalo chips and those and rag weed would make the fire to bake our bread and cook our meals. The old men and women would light their pipes with the chips.

After we got through the country, we came to large streams and plenty of timberland grass. We crossed one desert by driving at night. We could see Chimney Rock to our left. The Rock was used as a guide for weeks. It was ahead of a wide plain with little small streams at long distances apart. It did look no larger than a small chimney. The group stopped to go out to see it. Some of the men on foot turned back as it was much further away than it looked. My father and several of the men went on to it. It was 40 or 50 feet high with ledges that were wide enough to walk on. They went up part way but it was hard climbing. They found mountain sheep on a shelf 20 or more feet from the ground. The sheep jumped off when they saw the men. The rock was very fine grained. My father brought a piece of it to Oregon and it made a fine whetstone. He also found a mountain sheep horn which he also took on to Oregon.

There were only two forts on the trail. Each had a few soldiers. They were Fort Laramie and Fort Hall. By the time we reached the first fort, the company was running short for something to eat. We traded with the Indians for dried meat, dried salmon and a few small potatoes. Then we came to the high sage brush country. The next morning the Captain would single out the next wagon ahead until all the train had a turn to go to the front of the procession.

In time we came to timber and large streams. We had very little to eat by this time. What little we had we shared until there was nothing to divide. One night we camped by a creek that was lined with choke cherries. Everyone ate cherries. One woman had been sick for several days and was just feeling better; filled up on the cherries and died in the night. This was the only death we had in our company. The people by this time were eating anything they could get. Those that had tallow candles did well. The first family that came eating candles had a thousand dollars with them but couldn’t eat it. They used the rawhide that was wrapped around the wheels and the running gear of the wagons; they would scrape it and boil it. Our family had some dried salmon yet and gave our rawhide to those that had none. About this time we came to Fort Hall. Father bought flour at 50 cents per pint and coffee for the same price. We would boil raw hide and make soup of it with the flour and some dried salmon. We had no bread for three weeks.

There was a train of horse teams one day ahead of us that was better supplied than ours. The children would run ahead of our train to where the horse train had camped the night before. We’d pick up scraps of bread—if one child got more than one piece, he would divide. At night the families would camp off to themselves to keep the children from teasing for what others might have.

All these months, no one got discouraged. The men were out hunting for game—often they would get an antelope or small game. Two men went out and got lost and had nothing to eat but the moccasins on their feet. They overtook our train on the third day—they were nearly starved!

You may be wondering why we didn’t kill our stock to eat—we could not spare them. We had two yoke of oxen, two horses and one cow. If the oxen gave out, the horses were put in their place and the next day the oxen would go back to their routine after a day of rest. The milk we had to have for the small children. Three of them were younger than me. The youngest was 20 days old when we started our trip. [Laura is referring here to her siblings, Jasper, Alonzo, and 4-week-old Newton. All survived the trip].

When we came to different tribes the people bought whatever they could for food. We had plenty of money in the train but the Indians did not know the value of it. They would trade old clothes or some trinket for commodities.

When we came to Soda Springs3, we stayed over four days to rest the stock. When we came to the hot and cold springs, we stayed over one day and everybody did their washing. It was boiling hot. After the springs was the crossing of the rocky mountains. It took five days crossing with the men cutting timber and clearing the road and the women driving the teams. We crossed over where the town of Meacham [Oregon] now is. This was the Nez Perce Indian country. They were good to the “Lentens” as they called the white people. We brought stuff to trade.

There was a white man by the name of Smith or “Peg Leg Smith”4 with his Indian family. He had two hundred Nez Perce Indians (dressed in buckskin suits trimmed with bells and bead and their horses had bells and beads all over their saddles and bridles) come out to meet us. They marched two abreast until they came to the end of the train and then divided in single file each side of the wagons until we came to the river where we camped for the night. We came to the Snake River we traveled down the river, crossing it three times. We were by Steam Boat Springs close to the river. We stopped by a lone tree. It was a very large tree standing on a high knoll. We had watched it for miles and it had looked small.

The Nez Perce Indians went to Dr. Whitman5 and told him “The Boston Man had no muck a muck”—meaning that he had nothing to eat. Dr. Whitman had been to Washington D.C. to intercede for the country and had gotten home before our immigration.

The Hudson Bay Company tried to keep the Americans from crossing the mountains. Our trains were the first wagons to cross in what became “The Great Migration.” Dr. Whitman sent an Indian to meet the train and tell us to turn into his place near Fort Walla Walla. He had plenty of wheat and beef and the use of a garden. The people at the Whitman mission ground wheat in a large mill—like a coffee mill. The Doctor came around and said to grind a little at a time so as to give everybody a chance. The Doctor soon found out that my father was a millwright and he asked father to trim up the stones and fix the mission’s mill. In a few days, father had it going by horsepower by having a horse pull a sweep. Our stock was turned out to grass on the prairie. We stayed there four days.

Doctor Whitman supplied us with provisions and we journeyed on until we came to the Columbia River. Most of the families were taken down the river. Wagons and livestock were taken over the Cascade Mountains.

Forty miles above what is called the Celilo Falls6, the emigrants made rafts of logs to bring the families and baggage. Some of the wagons were brought along also. We were 8 days coming 40 miles. Near the falls we bought Chinook canoes from the Indians that lived along the river. We started down the river—staying mostly on the Washington side and passing through The Dalles rapids—or Dalls as it was called at that time. The women and children would walk around the rough places; then we would get in the canoes again. We passed the Indian village where the city of The Dalles now stands. The Mission was on the hill near the Old Fort Garrison. We camped on the Washington side. We were soaked as it rained all day so we built fires to dry out our clothes. Our supper consisted of the last of our flour that we brought from Dr. Whitman’s and a small piece of bacon for breakfast. We had a small piece of bacon about a pound for eight persons, we went on down the river, we met a Hudson Bay ***** [trader?] fetching from **** for the emigrants. Father hailed them, wanted them to let him have some provisions, they answered “go ahead, you will get to Vancouver soon.”

We went on, there was a high wind and we were blowed ashore near a small stream falling over the bluff in the Columbia. Made a fire, then father says, “I am going to get something to eat dead or alive.” He sharpened a stick [and] he went to this small stream. The salmon run up it until their backs were out of the water, he killed two. He named it Salmon Falls. They were so long and big he had to drag them on the ground. We ate salmon straight roasted on a log fire without salt or pepper and no bread. We went on in the morning going through the cascade rapids, going mostly on the Washington side. Mother would have to bail out the water out of the canoe all the time to keep from swamping. The roughest we walked around at one place towed the canoe around with a rope, then we would get in again. There were trees standing in the river all the way across scattered as far as the rapids was rough. They were red cedar perfectly round: the bark had peeled off and most of the limbs was off. The outside so white they would glisten in the sun. The Indians said long ago the mountain was across the sun. Father chipped some of them out with a hatchet taking the chips with us in this time.

Dr. Whitman had sent out an Indian to Vancouver to tell McLaughlin7 there was a man coming down the river that could build mills and to stop him, sending his name that was the way news was carried, writing and sending by an Indian. We got to Vancouver about nine o’clock that night, run in shore the night was intensely dark, so we nearly swamping our canoe on the cable of a sloop laying in near the landing. Just then there a man hailed us, “who comes there?”

By this time father was out of humor. He says, “it is none of your business.”

Then [the man] says “I am fixed to stand to here and hail any man that comes along” said he “waiting for a man that could build mills.”

Father told him his name.

“Come right in shore,” this man says. “I have stood here four days” says “my job is done.”

By this time there was some Frenchman came down to the landing, unloaded our canoe, stowing our things away, carrying the children up to the old fort. Supper was ready, the first whole meal we had for weeks, so our hardships was ended.

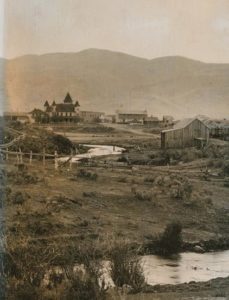

Started for Oregon City next morning. Doctor McLaughlin supplied us with provisions. Went up the Willamette opening by where Portland now stands, there was a man building a cabin in the timber there, and cutting timber. He called to father to come ashore. He says, “here is the Port, come to the Clackamas River, walked around the rapids.” Getting to Oregon City on the nineteenth of November 1843.

There was six dwelling houses, three of logs, with the bark on one for a Methodist church, a hued timber frame mill, split boards for weatherboarding, and split shakes for the roof, split boards for doors. This was one of the stations of the missionaries. There was a Catholic church and a school for the Indians. We went to school to Waller, one of the missionaries. The school was built of split boards, stood up end ways. There [was also the] mission store and Hudson Bay store. The ministers that were here at Oregon City were Reverends Gustaves Hindes, Wilson and Gray.

Some of the men went on ahead of the wagons with pack horse and were burning down timber to clear the land and to build houses for the families when they came down the river. A great many scattered out through the country and took up land had a hard time to get along that first winter, them that had stock had plenty of meat, and milk and butter. Flour was scarce, would buy wheat and boil it to eat. There was plenty of wild game and salmon. Father went right to work hewing out timbers for the mill. The Dr. hired men to build father a house to live in. [The Doctor also] hired men to work… sent for the millstones and other material for the mill. [Father and the men] worked all winter. Got the frame [up] with some were splitting shingles, others were sawing siding with a whipsaw, while others were splitting timbers for floors, got it in closed during the winter, had the ???. The Doctor then gave a party free to everybody. Everything was brought from Vancouver for the entertainment. Everybody seem[ed] to be there [and] danced all night in their homemade clothes.

Father finished the mill, it was painted white, called the White Mill. The next year [father] built the Island Mill, finished in 1845. At the present time, the Island Mill has been torn down, the White Mill has been turned into an electric power house. In 1846 in the fall [we] moved to north Yamhill [where father] built a sawmill. [He] built the old Newby gristmill where the McMinnville ?????, and a great many others. Built the first ***** in Jarvis, call[ed] the Jarvis mill where the town by that name stands, and different others in the country besides a great many bridges.

This written by Uncle Jake’s daughter

Laura A. Patterson nee Hawn.

Written in 1906

======================================

FOOTNOTES

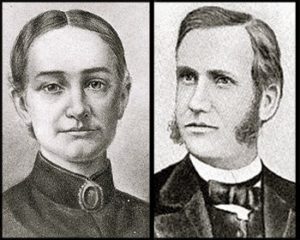

1Laura’s parents were Jacob Hawn (1805-1860) and Harriet Elizabeth Pierson Hawn (1818-1883). They are my great-great-great grandparents. They married on November 18, 1833. Ten years later (after numerous moves) the Hawn’s joined a wagon train headed to Oregon with their children, Jasper, Alonzo, Laura, and 4-week-old Newton.

Dr. Marcus Whitman—who was returning to Oregon after a trek East to ask for additional funding for his mission in what is now Walla Walla, Washington — joined the wagon train as well for awhile before heading out ahead as they neared the Columbia.

2 Jesse Applegate (July 5, 1811 – April 22, 1888) was an American pioneer who led a large group of settlers along the Oregon Trail into Oregon Country. He was influential in the early government of Oregon and helped establish the Applegate Trail as an alternative route to the Oregon Trail.

3 Soda Springs, Idaho was known as the “Oregon Trail Oasis” because of an abundance of springs and water in the area. Besides fresh water springs there are sulfur springs in the area. The Hawn wagon train arrived on August 26 at Soda Springs where they met John C. Fremont and his exploration party.

4 Peg Leg Smith’s real name was Thomas Long (October 10, 1801 – October 1866). Peg Leg was a mountain man who served as a guide for many early Western expeditions. Peg Leg’s other side hustles included fur trapper, prospector, and horse thief. During one expedition he was shot in the right knee by a local Indian; the wound and resulting infection forced the amputation of his right leg below the knee; legend has it that he performed the operation himself, and nearly finished it before passing out from blood loss and shock. He used a wooden leg afterwards and sometimes removed it to defend himself during fights.

5 Whitman – Dr. Marcus Whitman (1802 – 1847) and Narcissa Whitman (1808-1847). In the spring of 1836 the Whitmans, along with three others, left for Oregon with the intention of bringing Christianity to Native Americans in Oregon Country. They built a mission in the area which is now Walla Walla, Washington. In the winter of 1842, Dr. Whitman returned to the East to plea for additional money for the mission. The following summer Whitman then headed back in the same wagon train as the Hawns. At Fort Hall, Idaho Dr. Whitman decided to push forward alone but left the wagon train written directions for the remainder of the trip and details on camp sites. He supplemented this with notes pinned to trees or on stakes to help guide the emigrants.

In 1847 many Cayuse, who lived close to Whitman’s mission, died from an outbreak of measles. Remaining Cayuse accused Whitman of murder; they believed he had administered poison and was a failed shaman. In retaliation, a group of Cayuse killed the Whitmans and twelve other settlers on November 30, 1847.

As a child I dreamed of walking the Oregon trail with my parents with a secret hope I would become orphaned. I envisioned myself coming out of the Blue Mountains, skinny and barefoot, and so weak I could barely hold up my arms to show how raggedy my clothes were. I envisioned stumbling into Narcissa Whitman’s arms and being cared for by her. Her biography, was one of the first I read as a young child, was romanticized as biographies were back then when written for children. I have learned since that she was considered quite cruel and harsh, especially with natives in the area.

6 Celilo Falls are approximately 13 miles east of The Dalles, Oregon. It is the start of a long stretch of the Columbia that was ideally suited to Indian fishermen using spears, long poles with gaff hooks, and various types of nets – most commonly, dip nets. The name “Celilo Falls” was adopted after Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery reached the area, in October 1805.

Celilo was the oldest continuously inhabited community on the North American continent until 1957, when the falls and nearby settlements were submerged by the construction of The Dalles Dam.

7 [John] McLaughlin: (October 19, 1784 – September 3, 1857) was a French-Canadian, later American, Chief Factor and Superintendent of the Columbia District of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Vancouver from 1824 to 1845. He was later known as the “Father of Oregon” for his role in assisting the American cause in Oregon Country. In the 1840s, his general store in Oregon City was famous as the last stop on the Oregon Trail. As you can imagine, he is a controversial figure in Oregon history – as are most all white pioneers.